>> Brazil: Candidate Marina Silva’s Dubious Position on Gay Marriage, Abortion

Au Brésil, la campagne bat son plein à plus d’un mois du scrutin présidentiel. Alors que Marina Silva, la candidate écolo-évangéliste a le vent en poupe dans les sondages, Dilma Rousseff du Parti des travailleurs, la présidente sortante dont la réélection serait en péril, contre-attaque sur les questions de société, et notamment sur le thème des droits des homosexuels, très sensible pour sa rivale, chrétienne évangélique.

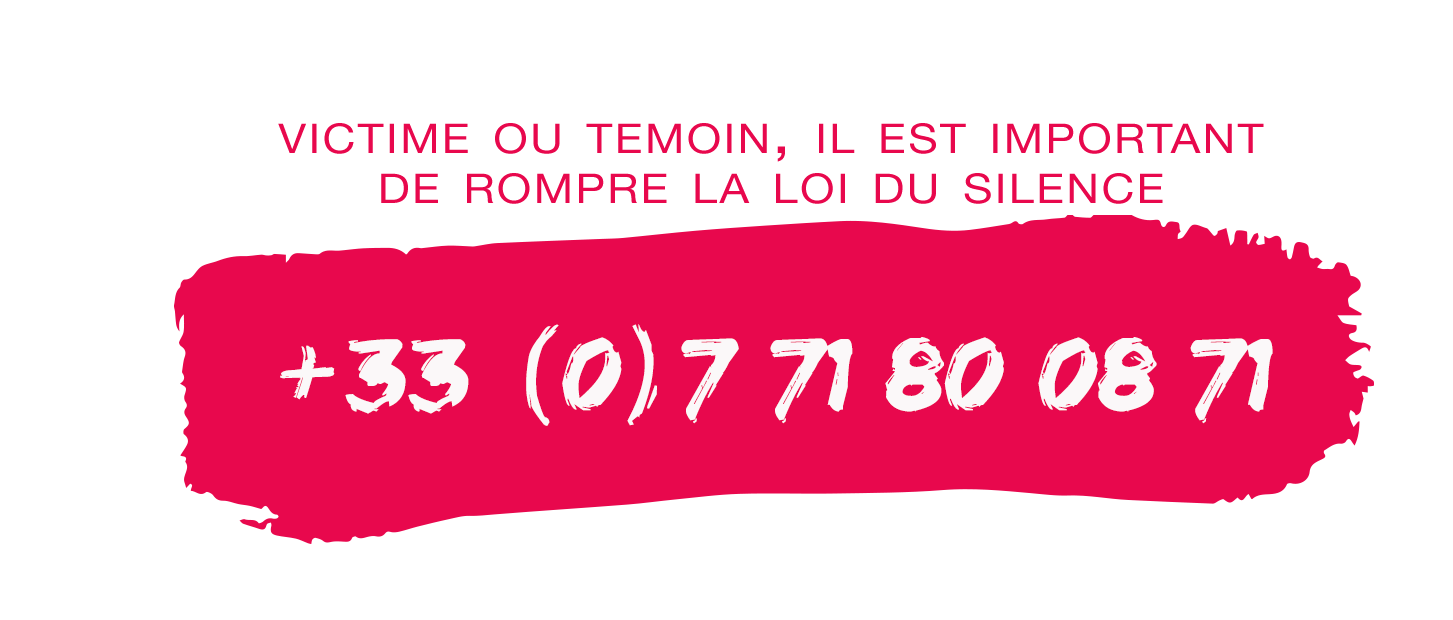

Dilma Rousseff cherche la faille, elle qui est au pouvoir depuis quatre ans et se trouve désormais menacée par Marina Silva, qui avait déjà recueilli près de 20% des voix il y a quatre ans. La présidente sortante martèle désormais son engagement contre la discrimination des homosexuels, alors que son adversaire tergiverse sur la question. Le programme initial de Marina Silva appuyait le mariage gay et les sanctions pénales contre l’homophobie.

Mais moins de 24h après sa publication, Marina Silva a fait marche arrière, en affirmant qu’il s’agissait de la mauvaise version du programme. Les articles polémiques ont ainsi été retirés. Entretemps, les chrétiens évangélistes, opposés au mariage gay et à un texte de loi pour garantir le droit des homosexuels, ont exercé de fortes pressions sur Marina Silva, qui fait partie de cette communauté chrétienne évangéliste, qui rassemble plus de 20% de l’électorat.

Une volte-face dénoncée par Dilma Rousseff, alors que Marina Silva prêche la rénovation de la politique.

>> Just before the first presidential debate, Silva was surging. According to a survey published by the Datafolha Institute on Friday, the aspiring candidate had not only overtaken formerly-second-placed Aécio Neves but had even caught up with incumbent Dilma Rousseff of the Workers Party (PT).

Silva, of the Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB), was tied with Rousseff at 34% each according to Datafolha, signalling a massive surge for the latecomer as just two weeks ago, the same institute’s prior poll showed Rousseff in first place with 36% of the vote while Silva was behind Neves (21%) with 20%. In the new poll, Neves of the center-right Party of Brazilian Social Democracy (PSDB) has slipped to third place with 15%.

Even better news came for Silva from Datafolha; in the likely event of a second round run-off vote between the top two candidates, Silva would defeat Rousseff by a margin of 10% as she would garner support from Rousseff’s opposition. The incumbent would receive 40% while Silva would receive 50% if the two face off in the second round. The Datafolha surveys are typically not far off the mark, and if the script follows the polling insitute’s predictions, the quick rise of Silva to Brazil’s highest office is nothing short of remarkable.

Silva was selected by the PSB to succeed Eduardo Campos, the former presidential candidate and Pernambuco Governor, after the latter passed away in a tragic airplane accident on August 13. Campos was traveling from Rio de Janeiro to São Paulo aboard a Cessna 560XLS+ when the jet crashed in a residential area of Santos, a coastal city some 80 kilometers (50 miles) southeast of São Paulo. Amid heavy rain and strong winds, air traffic controllers lost contact with the jet.

The 49-year-old Campos, a husband and father of five, was killed in the crash along with five others including his media advisor, two cameramen and two pilots. President Rousseff declared three days of mourning after his death and temporarily suspended her reelection campaign to fly to Recife for Campos’ funeral, which was also attended by former leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and the now-candidate, Marina Silva.

Less than two weeks after his passing, the PSB made the expected the decision to carry on the campaign with Silva, Campos’ running mate, as their candidate. Her running mate is Luiz Roberto ‘Beto’ de Albuquerque, a Federal Deputy for the State of Rio Grande do Sul and current President of the FSB’s Chamber of Deputies Block. Roberto Amaral, the President of the FSB, said his party was “heartbroken” over Campos’ death but “lucky to have such an outstanding replacement candidate in Silva.” In a relatively short press conference, Silva began her speech by thanking God for helping “guide the party through the difficult journey” after the death of Campos. It was an unsurprising opening given that she is a devout Evangelical Christian, a point that some have found issue with because they say that her faith might lead her to differ from the PSB’s stance on certain issues like abortion, same-sex civil unions and marriages and the separation of Church and State. Backers, on the other hand, say that she is a politician that just happens to be an Evangelical Christian, not an Evangelical politician in nature. She is loyal, they say, and she will keep the promises she made to Campos in regard to political compromise when she accepted the position of running mate.

Regardless, just after the first debate, her positions on certain issues were scrutinized and the question of the tug-of-war between her faith and political promises came up once again. As she presented her election platform at the debate event in São Paulo, Silva said she would introduce into law a constitutional amendment that would legalize same-sex marriage. She wants a “socially just country,” and thus, would also eliminate the red tape associated with the adoption of children by gay, bisexual and transsexual couples. The revelation was not surprising given Silva’s promise to fulfill the wishes of the party by keeping to the policies of Campos. However, it was members of her own faith, as Silva converted to pentecostal evangelicalism in 1998, that highlighted the contradictions between the political and religious facets of the candidate. Just hours later, the highly influential pentecostal pastor and author Silas Malafaia, a controversial figure known for his virulent opposition to homosexuality, abortion and other social issues, chimed in.

“Silva’s political platform is a shameful defense of the gay agenda,” he said and in the process, shared the statement to his nearly-one million Twitter followers. Brazil is the largest Catholic country in the world and will be for quite some time, but that population is dwindling, according to the Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE). Catholics comprised over 90% of the population in 1970 but by 2010, that number had fallen to 65% (143 million people) and their numbers are still falling. On the other hand, pentacostal evangelicalism and similar sects have been growing quickly since the early 1960s through the booming urban migrant community and by 2010, Protestants (mostly evangelical and pentecostal) were nearly 23% of the population or about 44 million people, making them a very important political ally. Silva, as a pentecostal evangelical herself, immediately drew large swaths of the population and this is likely the explanation for her surge in the polls. However, just as her membership in the faith draws support, it also draws pressures to adhere to the faith’s politically and socially conservative values. Indeed, less than 24 hours after she presented her plans for same-sex marriage and adoption, Silva’s campaign released a statement that said the media “misinterpreted” her proposal, which also contained measures that would criminalize homophobia, and that said proposal also contained a “mistake.” “The real goal of the candidate’s proposal was to guarantee the rights to civil unions for same-sex couples,” the campaign said, referring to a much more basic arrangement that brings certain benefits to couples but a measure that does not amend the constitution and does not carry constitutional protection. While some evangelical supporters were placated, albeit only slightly, by Silva’s change of opinion, other figures highlighted her position on social issues that clashes with her adopted party’s platform. Jean Wyllys, a professor, prominent gay activist and member of the Chamber of Deputies on behalf of the opposition Socialism and Freedom Party (PSOL) for Rio de Janeiro, said that “it only took a message from Pastor Malafaia for Marina Silva to forget the promises she made at a nationally-televised event less than 24 hours before to deny her own political agenda.” On the topic of abortion, the PSB has sought more freedom and choices for women, along with expanded reproductive health rights. Silva, on the other hand, has already affirmed that she will not seek to make any changes to the nation’s current law on abortion, which makes the procedure legal only in cases of rape, risk to the mother’s health and fetal anencephaly.

Thus, the law forces almost one million Brazilian women to undergo precarious and clandestine abortions annually. In the past, Silva has said that she is “personally not in favor of abortion” and instead, would focus on sexual education and policies that prevent unwanted pregnancies. As political units, referring to the Green and Sustainability Network parties she previously led, the parties voted in favor of the existing law after “internal debates.” When she ran for President in 2010 (and finished third), she said that making any changes to the existing abortion law is “the prerogative of Congress” and has previously supported a public debate and referendum on the issue, a position criticized by feminists because of the nationwide influence of religious groups and subsequent anti-abortion sentiments; any progressive referendum on abortion would fail and Silva knows this, they say. The second debate and subsequent polls should reveal if Silva’s religious and political sides clash and how the populace reacts. Silva is no stranger to political scrutiny, however, as she has previously served as Senator on behalf of f her Amazonian home state of Acre from 1995 to 2011 as a member of Rousseff’s Workers Party (PT) and with her history of focusing on social justice, sustainable development and environmental conservation, she was appointed Environment Minister by then-president Lula da Silva (PT) in 2003. After continually butting heads with figures in Lula’s cabinet over environmental issues, Silva resigned from her post in 2008 and switched her political affiliation, leaving the PT and joining the Green Party (PV) in 2009. The following year, she announced her candidacy for the presidential election of 2010, finishing third with a surprisingly high 20% of the vote behind runner-up centrist José Serra (32%) and the winner, Rousseff (47%). Silva founded a new party in February of 2013, the Sustainability Network party (Rede Sustentabilidade) but the party came up about 50,000 signatures short of the necessary 492,000 required by the Brazilian constitution for a party to be lawfully registered as an official political party. Over 100,000 signatures, double what she needed, were dubbed ‘invalid’ by the Supreme Electoral Court of Brazil, and her appeal of the ruling was denied. Because of this development and also because of a Brazilian law that demands candidates be officially affiliated with a party one year before the election (October of 2014), Silva joined the PSB along with several of her closest allies from her Rede Sustentabilidade party.

Avec rfi.fr