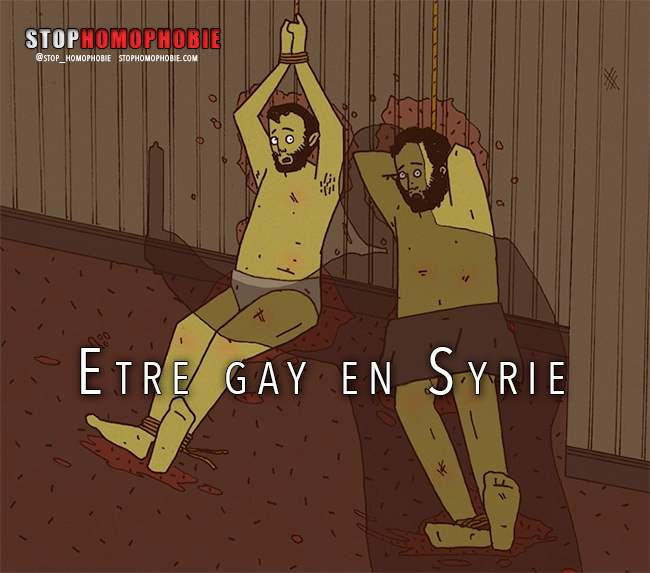

Coincée entre le régime de Bachar el-Assad et les islamistes, la communauté gay de Syrie doit lutter pour sa survie. Ce qui, pour ces hommes qui n’ont nulle part où aller, veut bien souvent dire quitter la Syrie, pour un ailleurs peu sûr.

Quand les rebelles syriens ont pris Racca en mars dernier, on aurait pu croire que la capture de cette cité nordique qui était jusque-là contrôlée par le régime du président Bachar el-Assad leur suffirait. Ils ne se sont pas immiscés dans la vie privée des citoyens selon Amir, un Syrien originaire de la ville.

Cette période de calme n’a hélas pas duré. Quand des groupes islamistes comme l’Etat islamique d’Irak et du Levant (ISIS) et le Front al-Nosra, tous deux apparentés à al-Qaida, ont commencé à monter en puissance, ils ont imposé leur interprétation de la justice islamique à la population.

«Petit à petit, ils ont entrepris de purifier la ville de ses éléments non islamiques, raconte Amir. Ailleurs, il y a des tribunaux, des procès… Mais avec eux, en un jour ou deux, ils peuvent décider de vous décapiter.»

La vie à Racca est rapidement devenue impossible pour Amir, qui est gay. Il a réussi à s’enfuir à Beyrouth. Il est sûr et certain d’être recherché par les djihadistes.

«Avant, avec le gouvernement syrien, on pouvait s’en sortir avec des pots-de-vin, nous explique-t-il. Mais certaines personnes sont tellement religieuses qu’elles résistent aux pots-de-vin.»

Tandis que les violences en Syrie se poursuivent, de nombreuses personnes se sont réfugiées auprès de leurs communautés ethniques ou religieuses pour y trouver la protection. Mais contrairement aux autres groupes minoritaires comme les chrétiens, les kurdes et les alaouites, les minorités sexuelles, et en particulier les homosexuels, ne bénéficient d’aucune protection de la part des institutions politiques, ethniques ou religieuses. Les homosexuels syriens ne sont nulle part à l’abri: dans tout le pays, ils ont été à la fois la cible d’attaques de militants pro-régimes et de miliciens islamistes. Parfois à cause de leur orientation sexuelle, mais aussi parce qu’ils sont perçus comme une proie facile à dépouiller au milieu d’une guerre chaotique.

Une violence qui peut aller jusqu’à la mort

En tant que responsable du programme au Projet d’assistance aux réfugiés irakiens (Irap), j’ai eu l’occasion d’interviewer des dizaines de réfugiés homosexuels syriens qui ont fui au Liban pour échapper à la persécution. L’Irap fournit une assistance légale à des réfugiés de toutes nationalités pour les aider à se réinstaller. De nombreux Syriens homosexuels ont accepté de témoigner pour m’aider à écrire cet article, sans que ce soit lié à l’assistance qu’ils ont reçue de la part d’Irap. Au cours de nos conversations, ces hommes ont décrit une culture de la violence véritablement choquante, même quand on prend en compte les innombrables et incroyables violations des droits de l’homme commises par la Syrie.

Les homosexuels qui sont toujours en Syrie ne doivent pas seulement éviter d’être découverts, puisque la capture d’une de leurs connaissances peut également représenter une menace mortelle. Amir se rappelle d’un de ses amis homosexuels, Badr, qui a été kidnappé l’été dernier par le Front al-Nosra, avant d’être torturé pour obtenir des informations sur d’autres homosexuels puis exécuté:

«Quelques jours plus tard, le Front al-Nosra a rassemblé des gens sur la place et a dénoncé un autre type en disant qu’il était pédé, raconte Amir. Ils lui ont coupé la tête avec une épée.»

Toute cette violence ne semble pourtant pas uniquement liée aux croyances islamistes. Il se pourrait qu’elle soit également provoquée par une simple envie de manifester son pouvoir et son autorité. Certains homosexuels ont eux-mêmes participé à des actes de violence à l’encontre de leurs semblables, en toute conscience du fait qu’ils risquaient d’être démasqués.

Imad raconte ainsi l’histoire d’une connaissance homosexuelle qui combat actuellement aux côtés d’un groupe islamiste:

«Il couchait avec un de mes amis homosexuels pour de l’argent, et puis il a disparu pendant quelques mois. En fait, il était en train de suivre un entraînement militaire à l’étranger. Il est revenu avec une longue barbe. Il est sûrement motivé par l’argent et par la protection qu’ils peuvent lui apporter.»

Les réfugiés qui fuient les violences en Syrie peuvent en général se contenter d’éviter les zones contrôlées par le groupe auquel ils s’opposent, mais dans le cas des homosexuels, les violences ne sont pas confinées à une seule zone géographique. Un résident de Damas, Najib, a fui sa maison après que son frère a découvert qu’il était gay. Son travail l’a conduit à rejoindre une banlieue de la capitale contrôlée par les rebelles, où il a entamé une relation avec un combattant islamiste. Le chef de la brigade, un musulman très conservateur, a commencé à avoir des soupçons sur leur relation, ce qui a forcé Najib à fuir une nouvelle fois pour se réfugier dans une banlieue plus proche de la ville.

Etat, opposition, tout le monde s’en prend aux homos

Un matin, des miliciens pro-régime l’ont arrêté à un point de contrôle. Najib a reconnu l’un des hommes, Kheder: il l’avait vu dans un parc qui servait de lieu de rendez-vous non officiel pour les homosexuels avant la révolution. Les hommes lui ont bandé les yeux et l’ont amené à l’intérieur d’un bâtiment, avant de lui réclamer 15.000 dollars s’il ne voulait pas être livré aux autorités de l’Etat.

«Après ça, ils m’ont dit de me déshabiller. Ils ont pris mon téléphone et m’ont photographié, raconte-t-il. Un autre type m’a mis un coup de pied dans la tête et m’a traité de prostitué. Après ça, ils m’ont violé.»

Najib a apporté de l’argent le lendemain, et a promis qu’il amènerait le reste de la somme dans les jours qui suivraient. Au lieu de ça, il a fui au Liban.

«Une personne homosexuelle en Syrie est prise entre deux feux: celui du régime, et celui de l’opposition, explique-t-il. Le problème, c’est que la plupart des gens trouvent normal qu’on s’en prenne aux homosexuels.»

Même si les actes de violence sont devenus de plus en plus communs ces dernières années, la persécution des homosexuels en Syrie date de bien avant le soulèvement. Le code pénal syrien stipule qu’un acte sexuel «non naturel» est un crime qui peut entraîner une peine de prison de trois ans. Le manque général d’acceptation de la société syrienne envers l’homosexualité a toujours forcé les homosexuels à vivre cachés et à se voir en secret pour éviter d’être arrêtés ou de subir les représailles d’un «crime contre l’honneur».

En 2009, la police a arrêté un groupe d’homosexuels à Racca après avoir obtenu un enregistrement de deux hommes en train de faire l’amour. Les policiers ont eu recours à la torture pour obtenir les noms d’autres homosexuels, avant de les arrêter eux aussi.

«Beaucoup de gens ont été attachés et roués de coup avant d’être interrogés. La plupart d’entre eux ont avoué leur homosexualité juste pour qu’on arrête de les torturer, m’explique Selim, un jeune homosexuel qui a fui Racca au printemps dernier, en parlant de la situation dans cette ville avant la révolution. Par contre, si on connaissait quelqu’un de haut placé au gouvernement, on pouvait s’en tirer. Tout le monde n’était pas arrêté. Certains subissaient juste un chantage alors que d’autres versaient des pots de vin à la police.»

Beyrouth, un asile qui n’est pas le paradis

Pour certains Syriens homosexuels, des membres de leur propre famille pouvaient représenter la plus grande menace d’être découvert. Joseph, un chrétien originaire de Deir Ez-Zor, une ville de l’est du pays, a fui la Syrie il y a quelques mois après avoir oublié d’éteindre son ordinateur dans un café alors qu’il se trouvait avec ses cousins. Il était en pleine conversation avec son petit-ami.

«Le lendemain, ils sont venus me voir et m’ont dit de quitter la Syrie, parce que j’allais déshonorer notre famille. Ils m’ont menacé de me tuer si je refusais de partir.»

Dans les 24 heures, Joseph est parti pour le Liban.

Même si Beyrouth est souvent considérée comme la ville la plus ouverte et libérée du Moyen-Orient, de nombreux réfugiés gays trouvent que leur situation n’y est pas beaucoup plus enviable. Dans la capitale libanaise, certains ont découvert qu’ils étaient exploités de la même manière que dans leur pays d’origine.

Hussein a fui le nord de la Syrie au printemps dernier, après qu’un membre de sa famille a essayé de l’assassiner en apprenant qu’il était gay. Il ne connaissait personne à Beyrouth et a commencé à dormir sur la plage. Il a été forcé de se prostituer pour survivre.

«Une fois, un type m’a ramassé pour coucher avec moi, me raconte-t-il. En fait, j’ai été violé par tout un groupe d’hommes libanais. Après l’agression, je suis retourné sur la plage parce que je n’avais nulle part où aller.»

Au cours de mes entretiens, quand je leur ai demandé s’ils ne pouvaient pas trouver un endroit plus sûr, la plupart des réfugiés homosexuels syriens m’ont toujours répondu la même chose: ils n’ont nulle par où aller. Cette situation doit changer: même s’il est difficile d’attendre plus de droits pour les homosexuels dans une société conservatrice en pleine guerre civile, les organisations d’aide aux réfugiés peuvent faire plus pour aider cette minorité oubliée. L’équipe devrait être particulièrement entraînée pour faire face aux besoins de cette population, on devrait développer les services d’aide aux hommes victimes de violences sexuelles, les individus les plus vulnérables devraient bénéficier d’un refuge plus sûr, et les réfugiés qui présentent le plus de risques devraient être déplacés dans un autre pays.

Yaman, un Syrien homosexuel qui a fui Kameshli, une ville au nord du pays, décrit son incapacité à trouver un logement à Beyrouth, et comment il a été ramassé dans la rue par un homme riche en échange de ses services sexuels. L’homme en question l’enfermait à l’intérieur de sa maison quand il partait travailler pour garder Yaman prisonnier.

«Après un temps, je ne pouvais plus le supporter, alors je suis parti, raconte-t-il. Je préfère encore être affamé et vivre dans la rue.»

>> Gay Syrians Are Being Blackmailed, Tortured and Killed by Jihadists

Even among the plush sofas and mood lighting of one of Beirut’s hippest bars, Ram shook with fear as he relived his ordeal. He turned his large green eyes from me to the translator and then back to me again, speaking in a low voice, even though we were the only people in the room.

« I think I was targeted for two reasons: because I’m a Druze, and because I’m gay, » he said. « They told us, ‘You are all perverts, and we are going to kill you to save the world’. »

Ram’s nightmare, which unfolded on a hot summer’s afternoon in Damascus, forced the then 19-year-old to flee his home for Beirut, with just a few hundred dollars in his pocket. Even in Damascus, the stronghold of Assad’s regime – where the elite still dance and drink cocktails in exclusive nightclubs – society has broken down into a chaotic quagmire where criminal gangs operate with impunity and radical Islamist groups are strengthening their stranglehold.

Maybe it was only a matter of time before Ram was picked out as a target. He is a Druze – a member of the small religious group that makes up just three percent of the Syrian population – and comes from a wealthy family well known for supporting Assad’s regime. From the beginning of the revolution he had known that these things could put him at risk. But his homosexuality was always a secret between him and his gay friends; he never thought that it could finally force him to flee.

« I got a phone call from my friend, » he recalled. « He asked me to come over to his house because he’d lost all his money and he needed my help. I could never refuse him anything, so I went there straight away. »

But Ram had walked into a trap.

« When I entered the house, a big guy was waiting – he had a beard and was holding a cattle prod. He told me to enter, and I was afraid that he would hit me with it, so I did as he told me. That house used to be a place of joy and happiness, but when I entered, it smelt of blood. » The friend who had called Ram was tied up and bleeding on the floor, together with another friend who had been tricked into coming to the house. Ram too was tied up and thrown down next to them.

Over the next few hours, Ram found out the extent of the torture they had been subjected to. « One said he had been raped with something and he was bleeding. He was crying because of the pain, but I think also because he was scared that they would do the same to me. Both had been hit on the testicles with the cattle prod. »

Three hours later, a group arrived at the house with a Range Rover. « We knew that they were planning to take us somewhere else because the house was in an area that wasn’t under the control of the rebels. They wanted to put us in the back and take us into FSA territory, » said Ram. « When they got me out to the entrance, I saw my chance. They hadn’t tied my hands properly and one of them had come loose. I kicked the man who was holding me in the balls and ran towards the souk. I knew that the army was there and so the kidnappers couldn’t come after me. I was screaming for help – I had no shoes on and my shirt was all torn. But at the same time I was thanking God to be alive. »

In his confusion and fear during the hours he was held captive, Ram never fully discovered who had kidnapped him or why. He says he has no doubt that they were members of one of the hardline Islamist groups that have emerged in Syria since the start of the civil war. He says that the man who tied him up in his friend’s house was Syrian, not from Damascus, but the north-eastern city of Deir Ezzor, which lies close to the border with Iraq and has endured some of the worst regime shelling and aerial bombardment of any major Syrian city.

More recently, it has been the scene of fierce clashing between moderate Free Syrian Army brigades and foreign al-Qaeda-affiliated Islamist groups, such as Jabhat al-Nusra, the largest and best known extremist group in Syria. Meanwhile, he believes that the four men who came to pick them up in the Range Rover were Chechens, easily identifiable by their dress, their skin colour and their language. They too have come into Syria in significant numbers over the past year, both joining and forming their own extremist fighting groups.

« I am sure that they were all members of Jabhat al-Nusra, because they talked a lot about religion, » Ram told me. « They kept telling me to say that Allah is the only God, and they told me that killing me is halal [allowed] because I am a Druze. »

Following his ordeal, Ram feared that he would be kidnapped again and killed if he stayed in Damascus. He packed a few belongings, gathered together all the money that he could and fled over the border into Lebanon to try to restart his life. Even here he is too scared to go into the Salafist areas of the city, terrified that his name is on the wanted lists of extremist groups. « My only message is that the radicals are a threat to the whole society, » he said. « I’m just thankful that they haven’t cut or burned me, and that I’m safe for the moment. »

Ram is one of seven gay Syrian men who I interviewed in Beirut this September. All of them fled Syria after their homosexuality was discovered and their lives were directly threatened in the chaos and radicalism that has engulfed their country. Even now, they are terrified that they will be discovered and captured again, but they agreed to speak out because they believe that what happened to them is also happening to many other gay men who are still trapped inside the country.

In northern Syria there are countless towns and villages where the regime has been driven out by the rebels, only to be replaced by another kind of tyranny, led by the scores of foreign jihadist fighters who have come to take part in what they believe is a holy war. When the Mujahideen brigades first appeared in Syria, they claimed that their mission was to help the FSA in their fight against Assad. In recent months, as the Islamist groups have turned with an ever-increasing ferocity on the moderate rebels they were meant to be fighting alongside, it has become starkly clear that this was never the case.

In many areas inside Syria the Islamist groups are now presiding over de-facto Islamic states, exerting social control through the Sharia courts they have established. There have been numerous eyewitness reports and video evidence of medieval-style punishments and brutal executions being meted out by the Islamists on members of minority religious groups, secularists and people accused of blasphemy. These men’s stories suggest that they are also targeting homosexuals, echoing what happened during Iraq’s darkest days. During the al-Qaeda insurgency against the US invasion there, gay men were regularly killed on the street in broad daylight. At that time, many gay Iraqis escaped to Syria, then one of the most tolerant countries in the Arab world.

The Islamists’ heartland now is al-Raqqa, a city that nestles on the banks of the Euphrates in the desert of northern Syria. It has gained a grim reputation as the scene of some of the worst atrocities being committed in the conflict, but when Shadi – a 27-year-old from Deir Ezzor – moved there in the middle of 2012 it was considered one of the safest areas in Syria. « I had to leave my home because of the shelling and fighting there, » he said. He was not alone – tens of thousands of Deir Ezzor’s war-battered civilians moved their families to nearby al-Raqqa in the hope of regaining some kind of normality. At that time, the city was under the complete control of Assad’s forces. There was no clashing, no bombing and no sign that either was about to break out.

In February of 2013, however, Jabhat al-Nusra scored a coup that would establish them as one of the most powerful rebel groups in Syria. In just a matter of days they overthrew the regime and took full control of the city; it was the first major town to fall entirely into the hands of a rebel group.

Jabhat al-Nusra quickly set about establishing Islamic law in al-Raqqa. One resident who recently escaped the city reported that the group had banned smoking and were punishing men and women who were wearing jeans. « One of my friends owned a shop that sold maternity clothes, but he had to close it because Nusra told him that he wasn’t allowed to serve women, » he said.

For Shadi, Jabhat al-Nusra’s ascent signalled the beginning of a reign of terror. « It started when one of my gay friends disappeared, » he said. « When he reappeared two weeks later it was obvious that he’d been at a Nusra training camp, and he started blackmailing all of his gay friends, using the photos and videos that he had of us. He told us that he was simply able to kill us by presenting us to Nusra with the proof he has that we’re gay. »

When two of Shadi’s friends refused to pay more money to their blackmailer, they paid with their lives. « He shot them with one bullet each, » said Shadi. « After that, rumours started going around the city that they had been shot because they were gay. We covered the rumours up at first by saying that they had been killed because they were informants for the regime, but the Nusra guy kept trying to blackmail the rest of us. »

Finally, tired of waiting for his money, the blackmailer went to Shadi’s parents with the photos. « My brother saw all the photos, » he said. « I’ve lost contact with all of them now except my mum. » He fled first to a village outside the city, and from there made the long and dangerous journey to the Lebanese border, along a route that took him through both regime and Jabhat al-Nusra checkpoints. « I was terrified of both of them, » he said.

Shadi’s tormentors were exploiting a fear that is almost universal among Syria’s gay community – the fear that their family will find out. « In Arabic society they don’t understand homosexuality, » Shadi explained. Opinion polls confirm his words; a study conducted by the Pew Research Centre earlier this year found that just three percent of people in Syria’s southern neighbour, Jordan, think that homosexuality is acceptable.

Shadi believes that his gay friend joined Jabhat al-Nusra as a means of self-preservation. But any gay men who do choose to join the extremists are themselves in a precarious position, and some will go to any lengths to keep their own sexuality a secret. Jihad, a 28-year-old from Homs, knew that his life was in danger when some of Nusra’s gay members began taking extreme steps to keep their homosexuality under cover. « My friend was killed after he slept with three Nusra members, » he said. « The neighbours said that they tortured him from 1AM until 4AM, then they shot him – once in the leg, once in the side, once in the shoulder and once in the head. I took his body from the police with his sister and buried him. »

After the murder, Jihad’s name was put on Nusra’s wanted list. « They said that we were doing immoral actions, so they put us on a list of people to be killed, » he said. « At the same time, I was also on the regime’s wanted list, because I joined a revolution page on Facebook. » Yet, while some Syrians have joined the extremist groups, the huge majority of the jihadist fighters have come in from outside. « Most of the Nusra leaders who came to al-Raqqa were Chechens, Tunisians and Saudis, » Shadi said. « They say that they want to clean the country of dirt by importing Islam. All the secular people and the minorities in al-Raqqa have left. The only people who are still there are the ones who agree with them, and the people who have no other options. » One of the men who killed Jihad’s friend came from a place that is uncomfortably close to home. « One of the Nusra guys was British, » he told me. « He said that he’d come to Syria to clean it of corruption. »

The majority of the gay men who have left Syria in recent months have, like Ram, Shadi and Kenan, fled from the prospect of torture or death at the hands of the extremist groups who are gradually strengthening their hold on the areas where the regime has retreated. Even in the areas where Assad is still clinging to power, the uprising has unleashed a wave of criminality. Wealthy families now live in fear of kidnapping, and gay men in particular are vulnerable.

Steve is a middle class Damascene who enjoyed a privileged lifestyle before the uprising. He worked in PR, earned a healthy salary and had a boyfriend, although he still kept his sexuality hidden from his family. When he was arrested at a gay party before the uprising, he was able to use his connections to get his case closed.

Then the revolution started. « Everything was chaos, » he said. « I started getting phone calls from someone who said that I had to give them money, otherwise they would tell my family that I’m gay. I changed my number but the calls carried on. I’m sure that someone in the intelligence services had put my name on a list, because after that I was stopped and questioned at every government checkpoint. »

At first, Steve paid the blackmailer. He got engaged to a woman in an attempt to stop the rumours that had started circulating about his homosexuality. But eventually, the thing he had been dreading happened: he was kidnapped. « I gave them $600 (£375), my phone and my bag and they let me go, » he said, « but the next day it happened again. »

Fearful that he might eventually be killed, and unable to confide in his family for support, he left and came to Beirut. « I’ve told my parents that people are just spreading rumours because they’re jealous of me, » he said. « So I think they’re confused – they don’t know what to think. But homosexuality is not accepted in this culture, and now criminals are using any weaknesses to make money. »

Even before the uprising, homosexuals were one of the most vulnerable groups in Syrian society, and that has left them vulnerable both to the Islamists who want to kill them for religious reasons and to the criminals who see them as an easy group to blackmail. « Gays are the easiest to abuse, and that’s why we’re abused everywhere, by everyone, » said Shadi.

Despite the differences in their ages and backgrounds, all of the men I interviewed had two things in common: they all fled Syria alone and none of them believe that they can ever go back. The gay friendship networks they used to rely on have crumbled, and their families cut contact when they found out about their homosexuality.

Patricia el-Khoury is a Beirut-based psychologist who provides counselling to some of the most traumatised gay men to have escaped Syria. She said that it is their isolation that causes the biggest psychological impact and makes them even more vulnerable than the tens of thousands of other refugees who have flooded into Lebanon. « Guilt is everywhere when I talk to these guys, » she said. « They feel that it is their fault that they have lost their families. »

Just like Shadi and Kenan, Pierre, 24, left al-Raqqa when Jabhat al-Nusra took control in February. Pierre’s family knew nothing of his homosexuality until February, when somebody gave his brother a video that showed him cross-dressing. He told the rest of the family, and then shot Pierre twice in the leg. As we talked, he pulled up the leg of his jeans to reveal an angry red scar across his ankle. « This one broke the bone, » he said.

When he learned that his brother had found him a bride and that he was due to be married, Pierre ran away to Lebanon. He has not had any contact with his family since. « I will never go back, » he said. « I can only go back if my parents change. The friends I had have left. There is nothing to link me there any more. »

Life as a gay man in Beirut – where the gay scene is far more visible than in Syria – may be easier in many ways, but the city’s open and, at times, extravagant scene can also come as a culture shock. « Although Syria and Lebanon are neighbouring countries, they are very different socially, » Patricia told me. « These guys have suddenly found themselves in a completely different environment. They are in a freer place, but often they are not prepared for it, so there is a tendency to go to extremes. There is a lot of prostitution on the gay scene in Lebanon, as well as drug use. »

Soon after arriving in Beirut, Jihad found himself in a difficult position. He had no money, few friends and the family that he would have relied on for support had cut him off. When he heard that there were job vacancies at one of the city’s hamams he decided to apply. But he quickly realised that the job involved sleeping with men for money. « It’s like selling yourself, » he said. « You don’t get a salary, just tips for having sex with the customers. » But in Lebanon, a country that is already struggling under the weight of over half a million Syrian refugees – and where the cost of living is sky-high in comparison to Syria – he has few other options.

Lebanese gay activist Bertho Makso told me that most gay Syrian men in Lebanon are either staying in cheap hotels where they have to share a dormitory with two or three strangers, or sleeping on the streets. In both situations they are vulnerable to theft and abuse. The lucky ones might find a friend who will host them for short periods of time. « The biggest problem for all of them is housing, » he said. « What I really want to do is to rent a couple of big apartments in Beirut that we can use as safe houses, to help these guys get on their feet when they first arrive here. But first we need to find funding. It’ll cost around $1,500 (£938) per month to rent two places; this is an expensive city. »

As the situation in Syria spirals further into chaos, refugees of all backgrounds keep pouring into Lebanon. By some estimates, one quarter of the population of this tiny, politically fragile country is now made up of Syrian refugees. And while many people in Lebanon feel sympathy for what is happening to their neighbours in Syria, a sense of resentment, anger and fear that the conflict may spill further over the border is palpable on the city’s streets. The recent car bombings and fighting between Sunnis and Alawites in the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli have only inflamed the existing anti-Syrian feelings further. The men I met may have escaped death, kidnapping and torture in their own country, but they have not reached safety yet.

« In Beirut, there are no problems for gay guys, » said Steve. « But there are many problems for Syrians. I still don’t feel secure here. »

Haley Bobseine

Responsable du programme Moyen-Orient du Iraqi Refugee Assistance Project

Traduit par Hélène Oscar Kempeneers

http://www.slate.fr/story/80939/syrie-homosexualite